So, I’ve been thinking a lot about Star Trek V and why I’ve been defending it all of these years. “Ugh,” you ask. “That stupid one where they go to find god?” WHY, YES, HYPOTHETICAL READER! That’s the one!

Now, why have I been thinking about Star Trek V? That I honestly don’t know. Though it probably has something to do with Twitter. You go and follow just a few Star Trek people on Twitter and suddenly your entire timeline is very, very Trekkie. And, when people gather to talk Trek, the conversation inevitably turns to Star Trek V and the extent to which is was or wasn’t terrible.

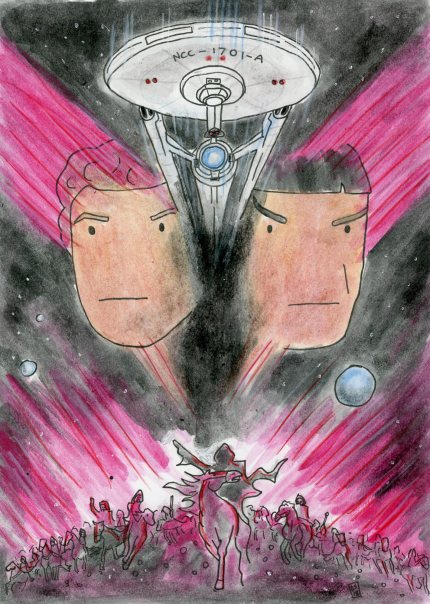

How It All Began? Lee Sargent’s Star Trek 365. Day 104: Star Trek V Poster. Follow, And Be Happy.

Star Trek V is controversial among fans for a number of reasons, most of which boil down to William Shatner, who directed the film and contributed to the script. Personally, I’ve always thought this is a little unfair and last week I sat down and sketched out an essay explaining why. Honestly, for me it is all about the story and how it is reflected in the production design. Yes, I’m talking about that story. The one where beloved sci-fi icons wander over to the Planet of God. Because over its runtime, the film juxtaposes the difference between belief and reality, and how a personal commitment to belief can affect the real world.

On Nimbus III, the Terran, Romulan and Klingon governments have set up a planet where peace will prevail. Each government will rule equally, and everyone will have a say.

Okay, okay. Why they would do this on a desert planet and not one of the kazillion apparently un- or under-inhabited lush planets those governments have visited over the years is beyond me, because it is obviously doomed to failure if there are literally no resources to go around. Nevertheless, they slap the descriptor, “The Planet of Intergalactic Peace” on it, believing they have found the way to create harmony.

Pictured: Perfect Location.

Predictably, this doesn’t work, to the point where we are told that the government had to take the extraordinary step of denying the inhabitants of the planet access to weapons. A lack of weapons would clearly lead to peace. Instead, people just made their own weapons and started threatening to pebble strangers to death over a bunch of holes (perhaps they were the exact number needed to fill the Albert Hall, and that’s why this character cared so much. YOU DON’T KNOW! HUSH UP!). Finally, planetary officials just gave up and started drinking themselves to death. Belief led directly to an unpleasant reality.

Enter Sybok. Think what you will about the character being a retconned brother to Spock, but Sybok, though his Vulcan mental abilities, injects fresh hope into the inhabitants of Nimbus III, and they, in turn agree to follow him. He believes that he knows where god actually lives on the physical plane, and given the evidence of what Sybok was able to do with their own spiritual pain, they believe him. Naturally, the resultant crisis means that the Enterprise and her crew must be called out of mothballs to save the planet and its supposed peace.

Without Circuit Breakers, As Usual.

It is significant that this is the first (and only) time that the crew was allowed to visibly age over their already clearly older bodies. Grey hair was embraced, and the makeup designs didn’t go completely out of their way to make everyone look smoother and less wrinkled. This was meant to be an older, more mortal crew. They were meant to be at a stage in life where humans are often described as seeking answers and seeking reconciliation with past choices. Previously, they only had themselves to lean on and offer each other reassurance — and, certainly, they still look to each other for that. Uhura and Scotty are taking a chance with a romantic relationship. Sulu and Chekov are best friends, and the traditional triumvirate are as close as they ever were.

When they meet their villain, however, Sybok shows even this indefatigable crew that, just maybe, they’ve been searching for more than just each other, that perhaps they need to pay more attention to their own spirituality and their own mortality. Sybok releases people from their torment by making them face their secret pain. We don’t get to see the pain of most of the crew members, but those we do see deal directly with these issues. Sybok allows people to come to terms with death and the circumstances of their own existence and releases the physical body from its spiritual trauma. From that standpoint, the supposed betrayal of Kirk by the rest of the crew is anything but. They’ve found answers to questions that, to one degree or another, they never even realized they had been asking and their desire is to share this with all of their friends. Further, their desire to help Sybok is justifiable compensation for what they believe he did for them. These responses are perfectly normal and human. But, again, belief doesn’t lead to a happy ending.

Pictured: Documentary Evidence.

Throughout the rest of the movie, these dynamics play out to varying degrees of subtlety and obviousness. And, yes, certainly, the overall movie is clunky. But, it is unique in its production design, largely because of budgetary concerns, but also because those differences help tell the story of a very human crew asking some deep questions about human nature, faith and reality. And, for once in the series, Star Trek isn’t putting these aspects of humanity onto an alien culture to make it easier for us to distance ourselves from the implications. Even the status of the Enterprise itself, broken and barely holding together, meets the dual goal of easing budgetary woes and makes the ship itself emblematic of the film’s central idea: even the ship is incomplete and it needs and seeks more.

Of course (since Shatner wrote the script), it is Kirk who refuses to even listen to Sybok and, thus, remains unswayed by his empathic abilities. It allows Kirk to be the savior of the day, and the smartest cookie in the room. And that is … problematic, at best. Personally, I wonder what it would have done to the film if Uhura, always portrayed as a woman very accepting of faith, if not of deep faith herself, had been the one to ask, “What does god need with a starship?”

Artist’s Conception. Sort Of: Day 110, Janeway Has A Question.

It’s a small change, but one with huge potential implications. it would have allowed Kirk to just as thoroughly fall into Sybok’s thrall, and it would have made all of the questions the film was pondering much more palatable. It would have allowed the one character who has been shown to have any experience in these matters to be the one to make the reality of the situation clear.

In the end, the Planet of Intergalactic Peace telegraphs the absurdity of the film’s often described plot from the beginning. We begin on a planet that can’t possibly exist even in the relatively rosy future of Star Trek, and we end on one, as well. At the outset, the desires of mortals and the coldness of reality are at odds, causing the characters to struggle to reconcile the two. Are they really trying to find god, or are they trying to find themselves, hidden in their fresh ideations of god? This leads to a very different answer to the film’s central question: that is what god needs with a star ship. Not for his own sake, certainly, but for the sake of his children and their own betterment.

Mind. Blown.

Star Trek V asked questions that the original crew had never really explored. Religion and what lies beyond really were The Final Frontier for the series. In the original series, anything vaguely supernatural would turn out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation. Religion was never even really a subject until The Next Generation and even then it was the kind of thing that aliens indulge in, rather than humans.

But Star Trek V tried to allow the crew an opportunity to explore aspects of their personalities we hadn’t previously been able to see. It gave us a fallible crew, in a fallible ship, caught in a trap that any of us might conceivably fall into, and it showed the way out. And, perhaps, a way to hold on to faith, when it might seem more reasonable to give up.

The series would return to this with Kai Wynn in Deep Space Nine, and, arguably, the subject is better and more thoroughly explored there. Sisko offers a human perspective on Bajoran beliefs, but, again, he doesn’t share them. Star Trek seems more comfortable leaving religion as an indulgence humans can’t afford. And, of course, Deep Space Nine explored this for seven seasons, instead of trying to cram it all into an hour and forty-five minutes. But Star Trek V tried, it really tried, to show the nature of human spirituality at the cusp of the 24th century.

Could it have been done better? The production was plagued by problems both internal and external. If Shatner had been able to get the special effects he wanted, if Shatner could have let go of what I’ve seen described as “A love letter to Kirk” — in fact, any change in the circumstances of production would have led to a different film, and it is quite possible that film would have been better. I feel, though, the movie that exists is more than capable of justifying itself — even if you might need to have a little faith to believe it. So, I’ve continued to champion it, Romulan cheerleader, boobied kitty-cat woman, water billiards and all. “But those are all shown in the same scene!” you say. “Right at the beginning of the movie! You have to push past all of them to even get started!” Yes, hypothetical reader, I know. I know.

Uh, Yeah. That’s The One.